|

Petition

to the President of the United States from 68 atomic scientists!!

July

17, 1945.

Dr.

Leo Szilard (1898-1964). |

|

In

July 1945, Leo Szilard—the father of the atomic bomb—sent

a petition to President Truman signed by 68 atomic scientists.

This petition asked the President to seriously consider the moral

implications of using weapons of mass destruction on the Japanese.

The President

was out of the country at the time—at Potsdam, Germany,

and he never saw the petition until his return on August 7—the

day after the bombing of Hiroshima.

General Groves

made sure that President Truman never saw the scientists' petition—until

it was too late!! |

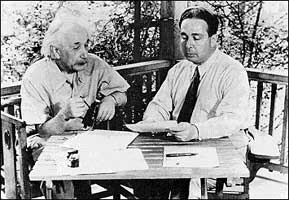

In 1934, Dr. Leo

Szilard filed a patent for the world's first chain reaction and the

concept of a "critical mass" to create it. In 1939, he was

instrumental in getting Dr. Albert Einstein to write a letter to Roosevelt

about the dangers of Nazi Germany developing atomic bombs.

|

In Aug. 1939,

Leo Szilard asked Dr. Einstein to write a letter to FDR about the

danger of Nazi Germany developing an atomic bomb. |

|

Nobody

in the U.S. government listened to Szilard at that time. Even

the Italian scientist Enrico Fermi was reluctant to pursue atomic

research.

Dr. Szilard

continued to pursue atomic research at Columbia University in

New York City and his frequent nightmare was that Nazi Germany

would develop the bomb first.

After the

Pearl Harbor debacle, everything changed.

Szilard and

Fermi worked together at the Rockefeller owned University of Chicago

to develop an atomic reactor. Szilard invented the concept of

the "breeder" reactor to create plutonium for fuel and

atomic bombs. |

Dr.

Szilard developed the atomic bomb for ONE reason only: as a precaution

against an A-bomb attack on the U.S. by Nazi Germany.

With the defeat

of Nazi Germany in May, 1945, he saw no reason for using the bomb against

Japan.

The 68 scientists'

letter

|

"Discoveries

of which the people of the United States are not aware may affect

the welfare of this nation in the near future. The liberation

of atomic power which has been achieved places atomic bombs

in the hands of the Army. It places in your hands, as Commander-in-Chief,

the fateful decision whether or not to sanction the use of such

bombs in the present phase of the war against Japan.

We, the

undersigned scientists, have been working in the field of atomic

power. Until recently we have had to fear that the United States

might be attacked by atomic bombs during this war and that her

only defense might lie in a counterattack by the same means.

Today, with the defeat of Germany, this danger is averted and

we feel impelled to say what follows:

The war

has to be brought speedily to a successful conclusion and attacks

by atomic bombs may very well be an effective method of warfare.

We feel, however, that such attacks on Japan could not be justified,

at least not until the terms which will be imposed after the

war on Japan were made public in detail and Japan were given

an opportunity to surrender.

If such

public announcement gave assurance to the Japanese that they

could look forward to a life devoted to peaceful pursuits in

their homeland and if Japan still refused to surrender our nation

might then, in certain circumstances, find itself forced to

resort to the use of atomic bombs. Such a step, however, ought

not to be made at any time without seriously considering the

moral responsibilities which are involved.

The development

of atomic power will provide the nations with new means of destruction.

The atomic bombs at our disposal represent only the first step

in this direction, and there is almost no limit to the destructive

power which will become available in the course of their future

development. Thus a nation which sets the precedent of using

these newly liberated forces of nature for purposes of destruction

may have to bear the responsibility of opening the door to an

era of devastation on an unimaginable scale.

If after

the war a situation is allowed to develop in the world which

permits rival powers to be in uncontrolled possession of these

new means of destruction, the cities of the United States as

well as the cities of other nations will be in continuous danger

of sudden annihilation. All the resources of the United States,

moral and material, may have to be mobilized to prevent the

advent of such a world situation. Its prevention is at present

the solemn responsibility of the United States—singled

out by virtue of her lead in the field of atomic power.

The added

material strength which this lead gives to the United States

brings with it the obligation of restraint and if we were to

violate this obligation our moral position would be weakened

in the eyes of the world and in our own eyes. It would then

be more difficult for us to live up to our responsibility of

bringing the unloosened forces of destruction under control.

In view

of the foregoing, we, the undersigned, respectfully petition:

first, that you exercise your power as Commander-in-Chief to

rule that the United States shall not resort to the use of atomic

bombs in this war unless the terms which will be imposed upon

Japan have been made public in detail and Japan knowing these

terms has refused to surrender; second, that in such an event

the question whether or not to use atomic bombs be decided by

you in the light of the consideration presented in this petition

as well as all the other moral responsibilities which are involved."

(Leo Szilard, His Version of the Facts,

pp. 211-212). |

General Eisenhower

said that the A-bomb was unnecessary!!

|

General

Eisenhower (1890-1969).

President of the U.S. from 1953-1960). |

|

General Eisenhower —the

Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe— was

in Berlin, Germany, when President Truman was meeting with Stalin

at Potsdam.

He was NEVER

consulted on the A-bomb decision. Leahy, Groves and Byrnes made

sure that President Truman was surrounded by "YES"

men!!

"The

incident took place in 1945 when Secretary of War Stimson, visiting

my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government

was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of

those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to

question the wisdom of such an act. I was not, of course, called

upon, officially, for any advice or counsel concerning the matter,

because the European theater, of which I was the commanding

general, was not involved, the forces of Hitler having already

been defeated. But the Secretary, upon giving me the news of

the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for

using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous

assent.

"During

his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of

a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings,

first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated

and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly

because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world

opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought,

no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking

some way to surrender with a minimum loss of "face."

The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude, almost angrily

refuting the reasons I gave for my quick conclusions."(General

Eisenhower, The White House Years, pp. 312-313). |

The military—like

the Vatican—is a HIERARCHY and no matter what the personal

opinions of the lower ranks it doesn't matter because once an order

comes from the top . . . it MUST be obeyed....That is why the Pentagon

is the greatest threat to the U.S. Republic. There is no place for

a MILITARY HIERARCHY—in this Republic or any Republic

. . . except to repel an invasion should it occur.

Official

Chronology of Leo Szilard—the father of the atomic bomb

Date |

Event |

1898 |

Leo Szilard

is born in Budapest, Hungary. |

1917 |

Drafted into

the Austro-Hungarian army. |

1922 |

Receives

a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Berlin. |

1927 |

Files the

first of 8 patents with Albert Einstein for an electromagnetic

pump, which became the basis of cooling systems in "breeder"

reactors. |

March

1934 |

Patents the

chain reaction concept in London, England. |

August

1934

|

Conducts

atomic research at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Invents

the Szilard-Chalmers effect for isotope separation. |

July

1939 |

Drafts a

letter with Einstein's signature to FDR warning about the danger

of Nazi Germany developing atomic bombs. |

Feb.

1942 |

Moves to

Chicago with other Columbia scientists becoming chief physicist

of the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago. |

Dec.

1942 |

With Enrico

Fermi put into operation the world's first chain-reaction atomic

"pile" (reactor) of their design |

Jan.

1943 |

Prepares

a memo on the first of three designs for a "breeder"

reactor (a name he coined) to create plutonium for fuel and A-bombs. |

March

1943 |

Becomes a

U.S. citizen. |

Aug.

1944 |

Proposes

a postwar arrangements for national and international control

of atomic energy (to curb what he predicted would be a U.S.-Soviet

arms race) almost one year before the first A-bomb was tested. |

March

1945 |

With an Einstein

letter seeks an appointment with President Roosevelt to present

scientists' views about wartime and postwar use of A-bombs. FDR

dies before their meeting. |

May

1945 |

Tries

to meet President Truman at the White House but is sent to Spartanburg,

South Carolina, to meet private citizen Jimmy Byrnes. |

July

1945 |

Organizes

a scientists' petition against dropping A-bombs on Japan, but

it never reaches President Truman because he is hustled

out of the country to Potsdam, Germany. |

1960 |

Receives

the U.S. atoms for peace award. |

1964 |

Dies of a

heart attack at his home in Ja Jolla, California. Dr. Szilard

should have received 2 Nobel prizes: One for PHYSICS and another

for PEACE but his anti-Fascist and pro peace with Russia views

cost him both. |

Vital Links

References

Eisenhower,

Dwight D. The White House Years. Doubleday & Co., New

York, 1963.

Lanouette,

William. Genius in the Shadows. A Biography of Leo Szilard. The

Man Behind the Bomb. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1992.

Szilard, Leo,

His Version of the Facts. The MIT Press. Cambridge, MASS.

1978

Back to Main Menu

|