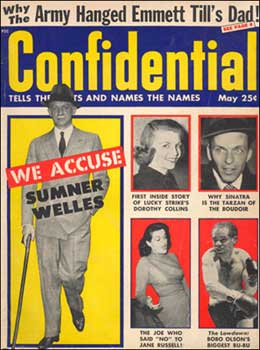

Confidential Magazine Exposé of Sumner Welles, March 1956

|

Confidential Magazine —a Hollywood scandal sheet—did an exposé on Sumner Welles in 1956. |

Confidential Magazine —a Hollywood scandal sheet—did an exposé on Sumner Welles in 1956. Ordinarily, the dignified Groton and Harvard "educated" Welles would only use a "rag" magazine like Confidential for shining his shoes. In this case, however, he consulted a top New York City law firm about bringing a million dollar lawsuit against the publisher... Back then a million dollars was a lot of money!! The law firm advised him to desist because the ensuing publicity would mean that reputable newspapers would have to mention his homosexuality. This exposé mentions his first solicitation of a Pullman porter on a train ride to attend the funeral of Senator Joseph T. Robinson in July 1937. Welles was appointed Under Secretary of State in May 1937. He practically ran the State Department until the scandal forced Roosevelt to fire his friend in 1943. |

|

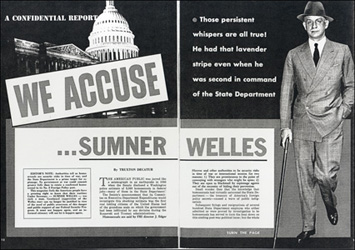

EDITOR'S NOTE: Authorities

tell us homosexuals are security risks in time of war, and the State

Department is a prime target for espionage. No government at war

could commit greater folly than to retain a confirmed homosexual

in its No. 2 Foreign Policy post. This magazine feels the American people have a pressing right to know that their wartime Under Secretary—SUMNER WELLES—was such a man. Continued suppression of the Welles story can no longer be justified in view of the need of public awareness of this danger and public support of our Federal Security Program. It must not happen again, and an informed citizenry will not let it happen again. |

By Truxton Decatur

THE

AMERICAN PUBLIC was jarred like a seismograph in an earthquake in 1950

when the Senate disclosed a Washington police estimate of 3,500 homosexuals

in federal jobs—many of them in the State Department.

The Senate's announcement that its Committee on Executive Department

Expenditures would investigate this shocking estimate was the first

real inkling citizens of the United States had of the grandiose scale

on which the government had been infiltrated by sex deviates during

the Roosevelt and Truman administration.

Homosexuals are said by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and other authorities to be security risks in time of war or international tension for two reasons: 1) They are promiscuous to the point of consorting with strangers who might be spies; 2) They are open to blackmail by espionage agents out of the necessity of hiding their perversion.

Small wonder then that the knowledge that homosexuals had virtually saturated the State Department—the treasury of America's foreign policy secrets—caused a wave of public indignation.

Subsequent firings and resignations of several hundred State Department employees who either admitted or were proved by investigation to be homosexuals has served to turn the heat down on this sizzling post-war political issue; but the whole story hasn't even begun to be told. A conspiracy of silence among Washington bigwigs and news correspondents has kept the public ignorant of how high homosexuals were able to penetrate the State Department, or how decisive was their influence.

This magazine cannot tell the full story. That is the task of Congressional investigative agencies and historians. But there is one dossier in CONFIDENTIAL'S files that should be helpful to the American people in realizing how near a man who would now be classified as a securiy risk, came to dominating American foreign policy.

Didn't Dare Print Truth About His Resignation

That man was Sumner Welles, a confirmed homosexual who was Under Secretary of State from 1937 to 1943, and second only to Secretary of State Cordell Hull in office and influence during some of the most fateful years in American history. Welles, now living in upstate New York, was actually Acting Secretary of State on many occasions during these years and might well have succeeded Hull—if knowledge of his promiscuity with men who were total strangers to him had not rallied opposition among certain apprehensive elements in the Roosevelt coterie.

Sumner Welles rose to the Under Secretaryship on the basis of his undisputed ability as a suave but hard-headed diplomat and his friendship with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It is questionable whether Roosevelt knew of Welles' perversion when he brought him into his administration as Assistant Secretary of State on April 6, 1933, only a month after his first inauguration.

Rumors that Welles was double-gaited, especially when liquored up as he often was, thrived, however, in the elite New York and Washington Society in which both Roosevelt and Welles were at home. They flourished too in the social circles of Cuba, where Welles served briefly as ambassador in 1933. These rumors didn't seep down to press circles until later, but by the time of World War II, Welles' prissiness was the butt of much pressroom humor around Washington.

Roosevelt Regime Couldn't Afford the Scandal

When Welles resigned as Under Secretary on Sept. 30, 1943, a score of newsmen knew the actual reasons. But no one dared print more than the "reliable report" that Welles was forced to resign by Secretary of State Hull. Hull was said to have demanded that Roosevelt choose between him and Welles, since fundamental policy differences which had arisen between them over United States-Argentine relations could not be compromised.

That was true, but it was really former Ambassador William C. Bullitt, a strong contender for the ailing Hull's job and Welles' archenemy, who organized opposition to Welles in the State Department and forced the issue. Bullitt threatened to expose the fact that Welles was a man morally ill. The Roosevelt regime couldn't afford the scandal, and F.D.R. had to sacrifice his old friend on the altar of respectability.

Subsequent developments showed it was one of Roosevelt's wisest moves. Hull resigned Nov. 27, 1944, and Welles probably would have succeeded him if Welles had remained in the State Department.

Welles

enjoyed Roosevelt's esteem and trust due to their similar New York Society

backgrounds and identical alma maters. But Roosevelt found

his tall, aloof and fastidious friend had a side to his character that

was more Bohemian than Social Register when Welles began to behave so

scandalously that F.D.R. had to assign Secret Service agents to keep

him out of trouble.

Roosevelt couldn't overlook Welles' peccadillos and the lavender stripe Welles had added to their old school tie after an incident involving Welles and a railroad dining car steward. The incident occurred in July, 1937, two months after Roosevelt had appointed Welles Under Secretary of State.

Ducked Detective Escort and Headed for Gay Time

Welles was en route by train to Little Rock, Ark. to represent the State Department at the funeral of Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson when the steward caught his eye. An invitation to visit Welles' compartment brought a complaint from the steward that was passed on by the railroad directly to the White House.

For almost a decade after that, the FBI stuck as close to Welles as a Spanish duenna to a wayward ward whenever he traveled to conferences or represented the President abroad. This was true when Welles attended the Panama conferences in 1939, when he toured the major allied and axis capitals of Europe in 1940, when he accompanied F.D.R. to the sea meeting with Churchill in 1941, and when he was a delegate to the Rio de Janeiro Conference in 1942.

Even after Welles' resignation from the Under Secretaryship in 1943, he was still a hot potato who had to be handled with care by police detectives in major American and Canadian cities, where his critical books on U. S. foreign policy made him much in demand as a speaker at conclaves on international affairs. Welles slipped his guards and nearly landed in headlines on one wild weekend in Cleveland in January, 1947. Police in that Ohio city still remember that incident as a nightmare.

Welles arrived in Cleveland Jan. 10th to speak before a meeting of the Council of World Affairs that had attracted such world figures as Alcide de Gasperi, Oswaldo Aranha, James Forrestal, V. K. Wellington Koo, Gen. Omar Bradley, Robert Schuman, James F. Byrnes, Francis Cardinal Spellman, James Carey, and Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg.

Welles spoke at the Cleveland Municipal Auditorium the next day and returned immediately to the Presidential Suite of the Cleveland Hotel for a session with a fifth of Old Grandad. Welles, who was so fond of whisky that he downed at least two double Manhattans before venturing out of bed in the morning, drank intermittently until 3 a.m. the next day. Then he ducked his detective escort and headed for a gay night on the town.

Found Him In Hamburger Joint

The frantic detective and a correspondent for a national magazine who joined the search found Welles in the Royal Castle Hamburger cafe, 15 Public Square, squiring a handsome youth. The boy admitted that the inebriated Welles had given him three $50 bills to persuade him to come to Welles' hotel suite. The correspondent persuaded the lad to fork over the cash, and the detective got Welles into a taxi only by promising to take him to the Club Vendome, a late hour pickup spot that was favored by Cleveland's most flaming homosexuals until it was later closed by police.

The detective and the correspondent took Welles instead to a side entrance of the Cleveland Hotel, where Welles grew obstreperous and refused to enter. His escorts subdued him but the correspondent's eye connected with Welles' flailing fists during the melee. The correspondent covered the final sessions of the Council meeting with a shiner that couldn't have been explained without precipitating a national scandal.

Welles' escorts put him to bed and took his clothes and money away from him to make sure he wouldn't resume his manhunt, but Welles was intent on seeing what bizarre pleasures Cleveland had to offer. The next evening, still in an alcoholic daze, Welles again gave his guard the slip after wheedling back his clothes, but not his money. This time a motorcycle policeman located the elegant former Under Secretary of State at the corner of Sixth Street and Prospect Avenue trying to get a ride to the Club Vendome.

He was hustled back to the hotel where a round-the-clock guard made sure he didn't leave until he departed Cleveland for good the next day with honors due to a visiting dignitary who might have been Secretary of State if a few persons in Washington had not been alert to the dangers inherent in homosexuality in 1943.

The fears of Bullitt and others who opposed Welles' continuance in public office were nearly realized in their worst aspect the following year when the secret of Welles' twisted sex drives came nearer to being told in headlines than at any time in his career.

Almost Frozen To Death

On the morning of Dec. 26, 1948, Welles was found semi-conscious in a field near his baronial 500-acre estate, "Oxon Hill Manor," overlooking the Potomac 10 miles south of Washington at Oxon Hill, MD. Welles' fingers and toes were frozen by seven hours' exposure in 15° temperature, and his clothes, covered with mud and sand, were frozen to his body.

The American press front-paged the story and, subsequent news of Welles' difficult recovery. But the only reason ever published for the accident was an allusion, unverified by Welles' physician, to the "possibility of a heart attack."

Did the flaw of Shakespearean proportions in Welles' moral character prompt him to leave his home at midnight, after imbibing liberally of Christmas cheer, for a nocturnal walk through the frozen fields of his lonely estate in search of 'forbidden satisfaction? CONFIDENTIAL can answer that affirmatively. Homosexuality, which drove Welles to the brink of notoriety, finally drove him almost to his death that winter night.

People Entitled To Know

These are facts the editors of this magazine feel the American public is entitled to know at long last. Not until 1947 did the Department of State, acknowledging itself "a vital target for persons engaged in espionage and subversion," institute a stringent security program providing for dismissal of any person who "has such basic weaknesses of character or lack of judgment as reasonably to justify the fear that he might be led into any course of action" detrimental to the security of the United States. For the first time "habitual drunkenness, sexual perversion and moral turpitude" were listed among those weaknesses of character.

By 1952, officials of Truman's Department of State were testifying repeatedly before Congressional committees that there were no known homosexuals left in the State Department. Yet the Eisenhower administration was still weeding homosexual "security risks" from the department as late as 1953.

At that time the New York Herald Tribune reported that Members of Congress familiar with the situation said some of the homosexuals apparently had been "protected" from questioning by former ranking officials of the Department of State.

If Sumner Welles, whose homosexuality was no secret in the White House, could rise to second in command of the State Department, it is not surprising that others who shared his weakness could rise to positions of rank, too. It is a chapter in American history that must not be repeated.

While staying at Hotel Cleveland's Presidential Suite, Welles offered $150 to entice a youth to his rooms. |

A cop and newsman collared Welles at a hamburger place, forced him to give up "MANHUNT." |

There were strange rumors when Welles was discovered half-frozen in a ditch in 1948— but no explanations. |