Can

you send out lightnings, that they may go, And say to you, "Here we are!"? (Job 38:35). |

|

Their

line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end

of the world (Psalm

19:4). |

WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT!

What hath God wrought! is from the Book of Numbers–the 4th book of the Old Covenant:

Surely there is no enchantment (sorcery) against Jacob, neither is there any divination against Israel: according to this time it shall be said of Jacob and of Israel, What hath God wrought! (Numbers 23:23).

Here is the dictionary definition of the word WROUGHT:

A past tense and a past participle of work.

adjective

1. Put together; created: a carefully wrought plan.

2. Shaped by hammering with tools. Used chiefly of metals or metalwork.

3. Made delicately or elaborately.

This short phrase from the Book of Numbers were the first words transmitted by the newly invented marvel of the electric telegraph.

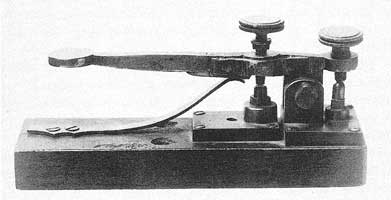

Telegraph comes from the Greek tele (far) and grapho (write) and was first used by French inventor Claude Chappe to mean FAR WRITER.

In 1844, time and distance were annihilated by the electric telegraph–the marvelous invention of Professor Samuel Morse. This miraculous invention later led to the telephone, radio, TV . . . and eventually the Internet!

|

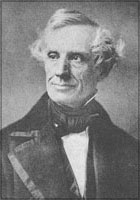

Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872). |

This was the most revolutionary invention since the printing press and the dawn of the telecommunications era.

Professor Morse sent the first telegraph message from the Supreme Court Room of the Capitol at Washington City. Annie Ellsworth, left, suggested the first message: What Hath God Wrought!

Professor Morse knew that Annie Ellsworth was divinely inspired to choose that phrase because he knew that all the glory belonged to Almighty God for the world changing discovery of writing remotely by using lightning or electricity.

Before electric telegraphy, most messages that traveled long distances were entrusted to messengers who memorized them or carried them in writing. These messages could be delivered no faster than the fastest horse.

Professor Morse first envisioned the electric telegraph in 1832

In 1832, Samuel Morse–the American Leonardo da Vinci– was returning to the U.S. from a trip to Europe. Morse was a very talented PAINTER and went abroad to study sculpture and painting in Great Britain, France, and Italy.

On the return voyage aboard the packet ship Sully, the conversation turned to the new discovered wonders of electro-magnetism:

In the early part of the voyage conversation at the dinner table turned upon recent discoveries in electro-magnetism, and the experiments of Ampère with the electro-magnet. Dr. Jackson spoke of the length of wire in the coil of a magnet, and the question was asked by some one of the company, "If the velocity of electricity was retarded by the length of the wire?" Dr. Jackson replied that electricity passes instantaneously over any known length of wire. He referred to experiments made by Dr. Franklin with several miles of wire in circuit, to ascertain the velocity of electricity; the result being that he could observe no difference of time between the touch at one extremity and the spark at the other. At this point Mr. Morse interposed the remark, "If the presence of electricity can be made visible in any part of the circuit, I see no reason why intelligence may not be transmitted instantaneously by electricity." The conversation went on. But the one new idea had taken complete possession of the mind of Mr. Morse. It was as sudden and pervading as if he had received at that moment an electric shock. All that he had learned in former years, the experiments he had seen in his boyhood, his studies with Professors Day and Silliman, the later and significant discourses of Professor Dana, and conversations with Professor Renwick, were revived, and began to form themselves into means and ways to the accomplishment of a grand result. He withdrew from the table and went upon deck. He was in mid-ocean, undique caedum, undique pontus. As the lightning cometh out of the east and shineth unto the west, so swift and far was the instrument to fork that was taking shape in his creative mind. (Prime, The Life of Samuel F. B. Morse, pp. 251-252).

Immediately after the ship's arrival in New York, Morse was eager to make his vision of the electric telegraph a practical reality:

Upon the Sully's arrival in New York in the autumn of 1832, Morse disembarked eager to begin work upon the telegraph; but the necessity of supporting himself and his children left little time for experiment and still less money for engaging in the construction of instruments. Furthermore, since there were no manufacturers of electrical appliances, the work had to be slowly and laboriously done by hand.

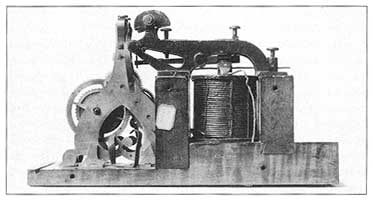

In 1835 Morse had the good fortune to secure an appointment as professor of the Literature of the Arts of Design in the new University of the City of New York, and took up his lodgings in the University building on Washington Square. Utilizing these quarters, not only as a studio and living apartment, but also as a workshop, he succeeded before the close of 1836 in completing his first, crude telegraph apparatus, and in devising a numerical code to represent the letters of the alphabet. (Thompson, Wiring a Continent, pp. 8-9).

For the next 5 years, working almost alone, and with very limited funds, Samuel Morse developed a rudimentary telegraph and then solved the greatest problem of all: transmission of electricity over long distances.

A battery that supplied a steady source of electric current had just been invented by Italian inventor Alessandro Volta. Volta's battery produced DIRECT CURRENT which is notoriously weak over long distances.

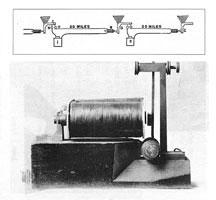

|

DC current loses a lot of its potential over long distances. Morse's relay reinforced this voltage with fresh batteries at each station.

|

The ingenuity of Morse's invention was its SIMPLICITY....As writing should contain no unnecessary words so a mechanical device should contain no unnecessary parts....The telegraph answered to that description and was sublime in its simplicity of operation.

Morse offered to sell his telegraph patent to the U.S. government for $100,000

After the successful test in 1844, Morse offered to sell his patent to the U.S. government for the measly sum of $100,000. That is equivalent to about $500,000 in today's paper "money."

Morse saw the telegraph as a natural adjunct to the Post Office. President Polk was very enthusiastic about the telegraph but was powerless to act without the approval of Congress.

|

Johnson refused to authorize the purchase of the patent for the paltry sum of $100,000.

Congress had to vote on any measure to appropriate funds for the telegraph, and with the opposition of Johnson, the government sponsored telegraph was doomed:

The Telegraph, no longer an experiment, was an accomplished fact. Speaking for itself, it required no champions on the floor of Congress, or in the public press. The extension of the line from Baltimore to Philadelphia and New York, and to all the cities of the land, was only a work of time. But the aid of Congress was sought in vain. An appropriation of $8,000 was made to support the line between the capital and Baltimore, while in its infancy, but further than that the Government declined to go. The sum named as the price for which the Morse Company would sell the Telegraph to the Government, was $100,000. The subject was discussed in the report of Hon. Cave Johnson, the Postmaster General, under President Polk. He was a member of Congress when the bill was before the House appropriating $30,000 for the experimental line, and was one of those who ridiculed the whole subject as unworthy the notice of sensible men. As Postmaster-General he said in his report, after the experiment had succeeded to the admiration of mankind: "That the operation of the Telegraph between Washington and Baltimore had not satisfied him that, under any rate of postage that could be adopted, its revenues could be made equal to its expenditures." (Prime, The Life of Samuel F. B. Morse, pp. 510-511).

With government support withdrawn, the telegraph was left entirely in the hands of private enterprise. After years of fierce competition, a company named Western Union emerged as the leading telegraph company in the U.S.

Morse aroused the hatred of Rome for his anti-Papal writings!!

With the success of the telegraph, Morse should have been a very wealthy man and able to return to his first love—painting....That was not to be however because Morse had aroused the hatred of the Roman hierarchy for his anti-Papal writings.

That was the real reason for the rejection of his miraculous invention!!

In 1830, during his European trip, while watching a procession of the host in Rome, he failed to take off his hat as a sign of respect to "Jesus" carried in the monstrance. According to the dogma of transubstantiation, the host is miraculously transformed into the body and blood of Christ and must be rendered divine honors. Morse failed to do this . . . and therefore lost his hat:

Later, on this same day, while watching a part of the ceremonies on the Corso, he has this rather disagreeable experience: -

"I was standing close to the side of the house when, in an instant, without the slightest notice, my hat was struck off to the distance of several yards by a soldier, or rather a poltroon in a soldier's costume, and this courteous maneuver was performed with his gun and bayonet, accompanied with curses and taunts and the expression of a demon in his countenance.

"In cases like this there is no redress. The soldier receives his orders to see that all hats are off in this religion of force, and the manner is left to his discretion. If he is a brute, as was the case in this instance, he may strike it off; or, as in some other instances, if the soldier be a gentleman, he may ask to have it taken off. There was no excuse for this outrage on all decency, to which every foreigner is liable and which is not of infrequent occurrence. The blame lies after all, not so much with the pitiful wretch who perpetrates this outrage, as it does with those who gave him such base and indiscriminate orders." (Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F. B. Morse: His Life & Journals, vol. I, p. 353).

After this experience at Rome, his eyes were really opened to the true nature of the Latin Church. When he arrived home, the Latin hierarchy was very active in subverting the nation through immigration and seeking taxpayer money for their parochial schools. As a Christian and a patriot, Morse decided to join the fight to save the public schools . . . and the nation!

In 1835, Morse published 2 small books which won him the undying hatred of the Roman hierarchy:

| 1. | Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration. |

| 2. | Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States. |

In between warning his fellow citizens about the threat from Rome, Professor Morse found time to invent the telegraph—the greatest boon to civilization since the printing press.

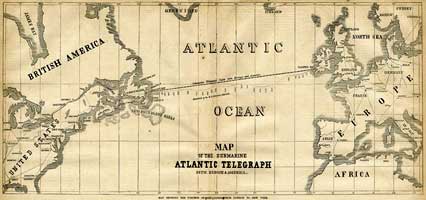

The first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858

Government support or not, nothing could halt the march of progress. By 1855, telegraph lines covered most of the eastern United States and the most ambitious plan of all was a transatlantic cable linking the United States with Great Britain.

Morse worked with another great Christian patriot named Cyrus W. Field to make the transatlantic cable a success.

|

Cyrus W. Field worked with his British counterparts to lay the first transatlantic cable. The USS Niagara and HMS Agamemnon laid the cable in the ocean. Messages of mutual admiration for the great feat were exchanged between Queen Victoria and President Buchanan.

|

On August 16, the first message sent across the cable was, "Glory to God in the highest; on earth, peace and good will toward men." Then Queen Victoria sent a telegram of congratulation to President James Buchanan through the line, and expressed a hope that it would prove an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem:

THE QUEEN'S MESSAGE To the President

of the United States, Washington:- |

President Buchanan responded that it was a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle:

|

THE PRESIDENT'S REPLY

To Her Majesty Victoria,

The Queen of Great Britain:- |

National hysteria broke out in the United States and England at the completion of the laying of the cable:

The celebrations that followed bordered on hysteria. There were hundred gun salutes in Boston and New York: flags flew from public buildings, church bells rang. There were fireworks, parades, and special church services. Torch-bearing revelers in New York got so carried away that City Hall was accidentally set on fire and narrowly escaped destruction. (Standage, The Victorian Internet, p. 81).

Unfortunately the transatlantic line broke after 3 weeks, and this interruption in communications almost led to a war between Great Britain and the U.S. over the Trent Affair.

The first transatlantic cable was sabotaged!!

Satan was desperate to prevent the laying of the transatlantic cable. Of course, most people don't even believe in the existence of the devil . . . and he likes it like that!

The euphoria over the laying of the first cable was short lived because the cable went dead after a month.

During the first attempt to lay the cable in 1857, someone among the crew members sabotaged the cable and it ended up on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

On the second attempt in May 1857, a furious storm (unprecedented in the North Atlantic at that time of year) arose and almost sent the cable . . . and the 2 ships . . . to the bottom of the ocean:

A week of this seemed all that any ship could take. But on Monday, the twenty-first, when it seemed the sea had done its worst and must by now have spent its strength, the most violent storm in memory raged across the North Atlantic. Wind howled in the rigging, tearing at the battered canvas; the ship pitched and shuddered, rising on giant waves to drop sickeningly into the troughs. A spar snapped in the bow; another dropped from overhead, bringing down everything attached to it. The starboard wing of the gallant American eagle figurehead was swept off to sea. Worst of all, the Agamemnon had disappeared in that churning mass of wind and rain and fury. In the crew's opinion the ship had foundered. (Carter, Cyrus Field: Man of Two World, p.150).

Satan can and does raise up hellish storms to foil God's purposes.....The Evil One raised up a furious storm to drown Joshua and His disciples on the Sea of Galilee (Matthew 8:24). When St. Paul was on his way to establish the Congregation at Rome, a furious storm arose which lasted for 14 days. (Acts 27:14).

|

On previous cable laying voyages, Whitehouse had excused himself by claiming "sickness." He waited in Ireland until the cable came ashore and then commenced his work of sabotage.

|

With the telegraph, the Trent Affair would have been resolved peaceably.

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) supervised the connection of the cable after the landing in Ireland. He then went home to visit his wife in Scotland and left Edward Whitehouse in charge:

After Thomson landed at Valentia, he went home to see his wife. He left cable refinements up to Whitehouse, who wanted no help. Toward the latter part of August, Thomson began receiving messages from Bright about transmission problems. He hurried back to Knightstown and discovered that Whitehouse had replaced his sensitive instruments with enormous induction coils five feet long and electrified with 500 cells that emitted up to 2,000 volts. Whitehouse had also inserted his own relay and Morse's electromagnetic recording instrument because he never understood Thomson's instruments well enough to use them. By the time Thomson restored his own instruments to the cable, Whitehouse's powerhouse had burned so many faults into the conductor that Thomson's devices would no longer work on lower voltages. To send a signal, Thomson had no recourse but to boost the voltage, and this continued to degrade the conductor by burning the insulation. (Hearn, Circuits in the Sea, pp. 132-133).

By running high voltage through the cable, Whitehouse ruined the greatest feat of engineering ever attempted by mankind. Another link was not established until after the Civil War.

President Lincoln used the telegraph to save the Union!!

God's great gift of this new technology came just in time to save the Union....President Lincoln used the telegraph to reach out to his generals in the field and the vast Union armies communicated frequently by telegraph.

|

A special branch of the army was organized called the Military Telegraph Corps with major Thomas T. Eckert commanding in Washington City.

|

Here is a quote from a book by David Homer Bates, manager of the war department telegraph office:

Abraham Lincoln has been studied from almost every point of view, but it is a notable fact that none of his biographers has ever seriously considered that branch of the Government service with which Lincoln was in daily personal touch for four years—the military telegraph; for during the Civil War the President spent more of his waking hours in the War Department telegraph office than in any other place, except the White House. While in the telegraph office he was comparatively free from official cares, and therefore more apt to disclose his natural traits and dispositions than elsewhere under other conditions. (Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, p. 3).

Unlike many of his subordinates, Lincoln was quick to grasp the new technology of the telegraph. His top priority was a telegraph linking the 2 greatest nations on earth.

Lincoln was anxious to establish communications with the Czar of Russia!!

President Lincoln was most anxious to establish a close diplomatic relationship with the great Czar of Russia–Alexander II....In 1861, the Czar sent his fleet to New York and San Francisco and thereby forestalled British military help to the Confederacy.

In his Annual Message to Congress, December, 1863, Lincoln, after referring to the arrangements with the Czar of Russia for the construction of a line of telegraph from our Pacific coast through the empire of Russia to connect with European systems, urged upon Congress favorable consideration of the subject of an international telegraph (cable) across the Atlantic and a cable connection between Washington and our forts and ports along the Atlantic coast and the Gulf of Mexico. In the latter scheme he took a deep personal interest, and he had a number of conferences with Cyrus W. Field, the chief exponent of ocean cables. (Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, p. 257).

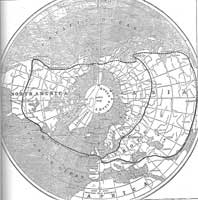

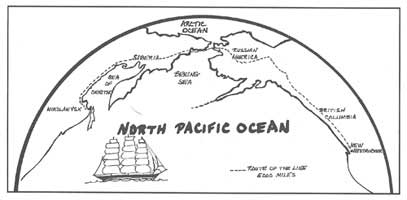

By 1861, the telegraph line had reached the Pacific Ocean and Western Union was given the mammoth task of extending it to Russian Alaska.

|

On July 1, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln granted Western Union the right of way from San Francisco to the British Columbia border.

|

President's Lincoln's assassination ended the Russian-American telegraph line and the noble enterprise of linking the 2 greatest nations on earth!

The excuse for ending the project was that the transatlantic cable made the Russian cable obsolete.

There was no direct communication link between Washington and Moscow until 1963.

Direct communication between the 2 greatest nations on earth would have prevented WWI, the Bolshevik Revolution, WWII, the Cold War etc., etc.

The Russian-American telegraph line was also sabotaged!!

It is almost beyond belief but the Russian-American telegraph line was also sabotaged.

By 1861, the telegraph line had reached the Pacific Ocean and Western Union was given the mammoth task of extending it to Russian Alaska.

|

Hiram Sibley was the president of Western Union.

At that time, Alaska was considered a frozen wilderness and the last outpost of the great Russian Empire. With the proposed Russian telegraph line, Alaska gained new importance:

When Western Union decided to build the line in 1864, Sibley had Seward and Russia's minister to Washington, Baron Edward de Stoeckl, write to Prince Alexander Gortchakoff, then minister of foreign affairs, and later chancellor of the Russian Empire, to pave the way. Sibley then traveled to Russia to replace Collins's thirty three-year grant with a perpetual lease. He thought a lease would avoid trouble with the Russian-American Company which held exclusive rights in that area. Sibley took a letter of credit for $750,000 with him to St. Petersburg, where he and Collins were presented to the Emperor on November 1, 1864.

The Emperor "promised his cordial cooperation in this great enterprise," and Sibley was entertained as a distinguished guest of the Empire.

During the discussions, Sibley told Prince Gortchakoff he would pay $750,000 for the rights to the strip of land desired for the line's right of way. "Why pay $750,000 for the rights of the Russian-American Company," Prince Gortchakoff asked, "when for that sum you can get the fee simple to the tract you want?" That led to a discussion of the purchase of the entire territory, but Sibley did not want Western Union to own and rule that huge wild area, so he urgently proposed the purchase to Washington. (Oslin, The Story of Telecommunications, p. 148).

Beginning in 1865, $3,000,000 was spent by the Western Union company to extend the line to the Bering Strait. The daring proposal was for ALL of Asia to be connected to the U.S. via Russia.

The great Czar of Russia was most anxious to see his empire connected to the U.S. so he negotiated with secretary Seward for the sale of Alaska to the U.S. government.

A race between the Russian and Atlantic cables!!

A race developed between the Russia-U.S. telegraph and the Atlantic telegraph. Both cables would have simply supplemented or complemented each other . . . but the Jesuits wanted no communications between the U.S. and Russia.

|

Cyrus Field was now so welcome in Great Britain that they called him Cyrus the Great and wanted to make him a "Sir."

The government gave top priority to a new cable and made the Great Eastern (their biggest ship) available.

Money was now no object and the Royal Navy gave him 2 battleships as a military escort.

This time, every care was taken against sabotage and the cable crew were not allowed to wear uniforms with pockets:

Every precaution had been taken against past mistakes. The cable crew were encased from head to toe in canvas. "They certainly look like convicts," Gooch wrote. The costume "covers their whole person and fastens in the back, and is without pockets, so that no one can take anything into the tanks without its being seen." On the bridge stood the Job-like Captain Anderson, "modest and grave, of few words, but seeing everything, watching everything, and ruling everything with a quiet power." The cable appeared to respond to this human discipline, paying out evenly at six knots. The polished hull of the Great Eastern slid so smoothly through the water that her stern propeller was disengaged to reduce speed.(Carter, Cyrus Field: Man of Two Worlds, pp. 247-247).

The success of the transatlantic cable sounded the death knell to the Russia-U.S. telegraph; even though the overland link was capable of 400 wpm, while the transatlantic cable was only capable of 40 wpm.

With the hegemony of the European cable, Great Britain became the hub of world communication . . . instead of the United States.

By sabotaging the cable, the Jesuits were determined to play the 2 greatest nations in the world against each other and reign over the ruins of both!

There was no direct communication link between Washington and Moscow until 1963.

Direct communication between the 2 greatest nations on earth would have prevented WWI, the Bolshevik Revolution, WWII, the Cold War etc., etc.

The Supreme Court ruled that Morse was the sole inventor of the telegraph!!

After the government refused to buy the telegraph patent, Morse had to turn to private enterprise. Fierce competition emerged among different companies over control of his invention.

Morse was frequently charged with plagiarism and he finally had to defend his invention all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

|

Honors poured in from around the world. Even the Sultan of Turkey honored him with a special diploma or decoration.

Here is an excerpt from the Morse patent trial before the Supreme Court:

The opinion of Justice Grier, concurred in by Justices Nelson and Wayne, contained these additional points: "I entirely concur with the majority of the court that the appellee and complainant below, Samuel F. B. Morse, is the true and first inventor of the recording telegraph, and the first who has successfully applied the agent or element of Nature, called electro-magnetism, to printing and recording intelligible characters at a distance; and that his patent of 1840, finally reissued in 1848, and his patent for his improvements, as reissued in the same year, are good and valid; and that the appellants have infringed the rights secured to the patentee by both his patents. But, as I do not concur in the views of the majority of the court, in regard to two great points of the case, I shall proceed to express my own." (Prime, The Life of Samuel F. B. Morse, p. 578).

Honors poured in upon Morse from around the world as all nations adopted the Morse code for communications. Prussia was one of the first nations to adopt it, and they put it to good effect with the defeat of the Austrians in 1866:

After passing a few months on the Isle of Wight, the Professor and family went to Dresden for the winter of 1867. Three months were spent in that delightful city. His presentation, at the court of the King of Saxony was a compliment paid to his distinguished services.

From Dresden, Professor Morse repaired to Berlin, where he was specially honored by those who were the best qualified to appreciate the magnitude and importance of his work. From Mr. Bancroft, the United States Minister, and members of the Prussian Government, he received constant attentions. He remained but a few days in Berlin, and was obliged to decline a presentation at court which was tendered him. (Prime, The Life of Samuel F. B. Morse, p. 703).

The Prussians again used the telegraph . . . and the train . . . to achieve a lightning victory over the French in 1870 . . . which finally led to the liberation of Rome on September 20, 1870.

Morse home in Poughkeepsie, NY. |

|

The body of the "Lightning Man" awaits the great Resurrection morning in Greenlawn Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY.

Samuel Morse is the real father of modern telecommunications because his invention led to the telephone, radio, TV . . . and eventually the Internet!

Nikola Tesla completed the electrical revolution begun by Professor Morse!!

Professor Morse saw by experiments that DC current lost at lot of its potential when covering long distances. This is now proven mathematically by Ohm's Law.

This voltage loss led to his invention of the relay or repeater which reinforced the voltage with a battery at every station.

|

3 phase rotating magnetic field. |

Like Morse, Tesla had powerful enemies (Rockefeller, Morgan, Edison) who opposed his new inventions.

Morse envisioned the electric telegraph during an ocean voyage from Europe to the United States. Tesla saw the rotating magnetic field during a walk in the park in Budapest, Hungary.

Morse had his patent stolen and had to defend his invention against frequent infringements. Most of Tesla's great inventions were stolen and he ended up a virtual pauper when he died.

Tesla's inventions are just too many to list....He completed the electrical revolution begun by the great Christian patriot, Samuel F. B. Morse.

Vital Links

References

Bates, David Homer. Lincoln in the Telegraph Office. Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1995.

Carter, Samuel, Cyrus Field: Man of Two Worlds. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1968.

Gordon, John Steele. A Thread Across the Ocean. The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable. Walker & Co., New York, 2002.

Hearn, Chester G. Circuits of the Sea. The Men, The Ships, and the Atlantic Cable. Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 2004.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought! The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford University Press, New York, 2007.

Morse, Samuel, Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration. E. B. Clayton, New York, 1835.

Morse, Samuel, Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States. American and Foreign Christian Union, New York, 1855.

Morse Edward Lind. Samuel F. B. Morse: His Life & Journals. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston & New York, 1914.

Neering Rosemany. Continental Dash. The Russian-American Telegraph. Horsdal & Schubart, Ganges. British Columbia, 1989.

Oslin, George P. The Story of Telecommunications. Mercer University Press, Macon, Georgia, 1992.

Prime, Samuel Irenaeus. The Life of Samuel F. B. Morse. Appleton & Company, New York, 1875.

Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet. The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-Line Pioneers, Walker & Co., New York, 1998.

Thompson, Robert Luther. Wiring a Continent: The History of the Telegraphy Industry in the United States 1832–1866. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1947.

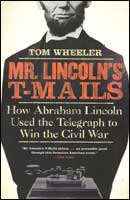

Wheeler, Tom. Mr. Lincoln's T-Mails. The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2006.

Copyright © 2016 by Patrick Scrivener