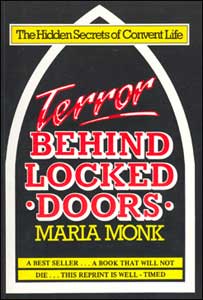

IT was over a hundred years ago—in 1835—that Maria Monk, making her way from Canada to New York, startled the world with her "awful disclosures" of life in a Convent and, since that time, controversy has raged over her story. It was, of course, only to be expected that its publication would immediately be followed by the denials of the people concerned in it. Virulent attacks were made upon the book and every effort was made to destroy public confidence in the character of its author. Maria Monk, however, refused to be shaken in her testimony, and steadfastly avowed the truth of what she had written. To those who doubted or disbelieved her statements she made the following challenge. "Permit me," she said, "to go through the Hotel Dieu Nunnery at Montreal with some impartial ladies and gentlemen, and they may compare my account with the interior parts of the building, into which no other persons but the Roman Bishop and Priests are ever admitted; and if they do not find my description true, then discard me as an impostor. Bring me before a court of justice—there I am willing to meet Latargue, Duireme, Phelan, Bonin and Richards, and their wicked companions, and the Superior and any of the Nuns before a thousand men." The attacks made upon her veracity, as well as the recollection of what she had undergone, distressed and agitated her, and she threw herself upon the sympathy of the public for being an unwilling participant in the guilty transactions which she described. At the time of penning her manuscript, she had no means of telling what the publication of her disclosures would mean. Before the manuscript was published, she submitted herself to examination by several intelligent, disinterested persons, who satisfied themselves that the allegations she made were true. The newspapers took sides both for and against her. One New York Catholic paper even went so far as to propose that the publishers should be lynched. Anonymous handbills were circulated, declaring the work to be a libel, inspired by Protestant Clergymen. Affidavits were published in some newspapers, tending to undermine her character. Maria, however, found stalwart friends, who upheld her veracity, and she continued to refute the allegations made against her by her attackers, and continually called for those who would confirm the truth of her story to be produced; for, as she stated, there were living witnesses who ought to be made to speak, without fear of penances, torture or death, and she lived in the hope that the testimony of these witnesses would be eventually allowed to confirm her statements. At the same time, she expressed her doubts as to whether those witnesses had been allowed to live after the Priests and the Superior had seen her book. She was tormented with the possibility that the wretched Nuns in their cells had already suffered for her sake, and that Jane Ray, who figures prominently in the disclosures, had been silenced for ever, or would be murdered before she would be able to add her important testimony to Maria's This book has stood the test of time. For over a hundred years it has been a best seller. Its author could surely not have foreseen the tremendous circulation which her words would eventually achieve. She herself died in 1850, her later years clouded over by the recollection of the deeds that had happened in her unfortunate life. But she died resigned, for death had come as a relief from the misery which had dogged her footsteps through life. As she herself stated " Speedy death in relation to this world can be no great calamity to those who lead the life of a Nun. The mere recollection of it always makes me miserable. It would distress the reader should I repeat the dreams with which I am so often terrified at night, for I sometimes fancy myself present at the repetition of the worst scenes that I have hinted at or described. Sometimes I stand by the secret place of interment in the cellar; sometimes I think I can hear the shrieks of the helpless women in the hands of wicked men and sometimes seem actually to look again upon the calm and placid features of St. Francis as she appeared when surrounded by her murderers. " I cannot banish the scenes and characters of this book from my memory. To me, it can never be like an amusing fable, or lose its interest and importance. The story is one which is continually before me, and must return fresh to my mind with painful emotions as long as I live. With time and Christian instruction, and the sympathy and examples of the wise and the good, I hope to learn submissively; to bear whatever trials are appointed me, and to improve under them all." In preparing this new edition, nothing has been taken from or added to the terrible story which Maria Monk's pen has written. Some of her more archaic and outmoded phrases have been replaced by more modern expressions ; the intention being to render the work more readable to the average person. Care has also been taken to select attractive and readable type. But her damning indictment of the hidden secrets of a Nun's life in a Convent remains stark and vivid in its intensity.

|